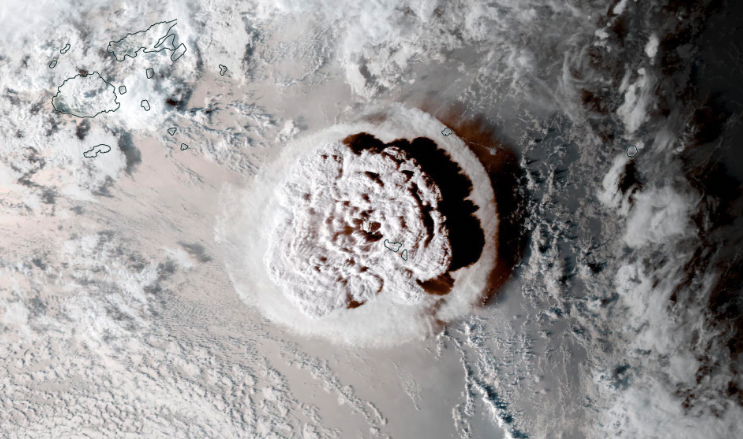

When an underwater volcano in Tonga erupted on January 15, 2022, the volcano erupted and released clouds of ash and steam into the ocean, which caused intense lightning. This was no ordinary storm.

Hunga is famous for his temper, but he has outdone himself. That storm now boasts the most lightning strikes ever recorded on Earth. Above the Pacific Ocean, the lava cloud was terrifying and flashed with lightning visible about 192,000 times during the 11 hours the volcano erupted (that’s 2,615 flashes per minute). Lightning struck up to 30 kilometers (19 miles) in the air—another record, striking even storms with large cells.

Led by volcanologist Alexa Van Eaton of the US Geological Survey, a team of researchers who looked closely at what they saw from the Hunga eruption and the typhoon found that no one had ever recorded lightning of this magnitude. “Our findings show that lava of sufficient strength can create its own climate, maintaining electrical conditions at heights and rates not seen before,” Van Eaton and his team said in a study recently published in Geophysical Research Letters.

Making lightning

Lightning is made up of positively or negatively charged particles created in a turbulent atmosphere. For a while, the air acts as an insulator, keeping the particles in place. But if the charge is too high, it can cause damage to the air, allowing the electricity to flow so that the opposite charges are aligned. Their meeting place may be on Earth or where opposing charges have gathered within a thunder cloud.

The interstellar lightning flashes seen during the Hunga eruption are thought to have been produced by high-energy waves called gravitational waves. As this passed through the clouds above the mountain, it caused a change in the atmosphere and created enough turbulence to produce lightning.

Although Mount Hunga began erupting on December 19, 2021, it was at its most dangerous on January 15, when lava erupted about 58 km (36 mi) into the sky. There were two geostationary satellites, NOAA’s GOES-8 (using the Geostationary Lightning Mapper or GLM) and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Himawari-8, which observed the phenomenon as it changed. Through this data the researchers found four stages of eruption.

Cross sections

In the first phase, satellites saw the lava rise and fall, but there was no sign of lightning. The second part was very intense. Magma, water vapor, and other gases from the volcano shot up into the atmosphere at incredible speeds, blasting through the mesosphere, where the summit had previously erupted, and into the stratosphere, where it reached its maximum height. This created a large umbrella cloud in the stratosphere and a smaller cloud below it in the tropopause. The cloud in the sky is thought to have been 40 kilometers (about 25 miles) long. There was so much thrown into the atmosphere that it sent gravitational waves traveling at a speed of 80 meters per second, creating ripples in the clouds, especially the cloud in the sky, and expanding the lightning rings.

The GLM instrument saw intense lightning as the upper umbrella cloud began to move away from the mountain and reveal its smoky atmosphere. The explosions and lightning subsided a bit, but increased again in the third quarter, and only in the fourth quarter did the intensity begin to fade.

Unfortunately, when the waves got higher than 30 km (about 19 mi) above sea level, the GLM became difficult to observe, and the lightning was sometimes invisible. Van Eaton and his team think that this was caused by a lightning flash that was too low or too high for the satellite to be captured (it is possible that it was too low because it had to be seen from a high altitude).

“This event continues to push the boundaries of our understanding of how volcanic eruptions affect the world,” Van Eaton said in the study.

Because he and his team discovered that explosions can amplify lightning, their findings will make it easier to assess the danger to aircraft from lightning and ash clouds that can block eyes. He plans to continue studying this field to learn more. Sometimes, special effects in nature can look more real than what is in the movies.

Geophysical Research Letters, 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL102341 (About DOIs).

Elizabeth Rayne is a creature that writes. His work has appeared on SYFY WIRE, Space.com, Live Science, Grunge, Den of Geek, and Forbidden Futures. When he’s not writing, he can move, draw, or play like someone no one has ever heard of. Follow him on Twitter @quothravenrayne.

#explosion #electrical #paste #caused #deadliest #lightning #strike #Ars #Technica