Daniel Huber is an astrophysicist at the University of Sydney.

The search for planets outside our solar system – exoplanets – is one of the fastest growing fields in astronomy. Over the past few decades, more than 5000 exoplanets have been discovered and astronomers now estimate that there is approximately one exoplanet for every star in our galaxy.

Many recent experiments aim to identify planets like Earth suitable for life. These efforts focus on so-called “main sequence” stars like our Sun – stars that are powered by fusing hydrogen atoms into helium during their lives, and are stable for billions of years. More than 90% of all exoplanets known to date have been found around massive stars.

As part of an international team of astronomers, we studied a star that looks like our Sun for billions of years, and found that it has a planet that should by all means destroy it. In a study published Thursday in Nature, we put a picture of the planet’s existence — and offered some possible answers.

READ MORE:

* The giant planet Jupiter has found an orbiting star in the Milky Way

* A backstage astronomer discovers a mysterious and massive planet

* Astronomers discover a giant planet orbiting a small star. The way it was created is unexpected

Seeing our future: big red stars

Like people, stars change as they age. Once a star has used up all of its hydrogen, the core shrinks and the outer envelope expands as the star cools.

During this “red giant” evolution, stars can grow up to 100 times their original size. When this happens to our Sun, in about 5 billion years, we expect it to expand so much that it will swallow Mercury, Venus, and possibly Earth.

Eventually, the core becomes hot enough for the star to start fusing helium. During this time, the star returns to about ten times its original size, and continues to burn steadily for millions of years.

We know of hundreds of planets orbiting red giant stars. One of these is called 8 Ursae Minoris b, a Jupiter-mass planet in an orbit that keeps it only about half as far from its star as Earth is from the Sun.

The planet was discovered in 2015 by a team of Korean astronomers using the “Doppler wobble” technique, which measures the Earth’s gravitational pull on a star. In 2019, the International Astronomical Union named the star Baekdu and the planet Halla, after the highest mountain on the Korean peninsula.

A world that should not exist

Analysis of Baekdu data collected by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) telescope has made surprising discoveries. Unlike other red giants we have found to host exoplanets at close orbits, Baekdu has already begun mixing helium in its core.

Using the methods of asteroseismology, which studies the waves inside the star, we can determine what the star is burning. For Baekdu, the liquid waves are a clear indication that he has begun to burn helium at the core.

What he found was surprising: if Baekdu was burning helium, it would have to be very large in the past – so large it would have to sink the planet Halla. How will Halla survive?

As is often the case in scientific research, the first step was to rule out the least plausible explanation: that Halla never existed.

Indeed, some false predictions of planets orbiting red giants using the Doppler shift method have later been shown to be false due to long-term variations in the behavior of the star.

However, what he saw later proved that Halla was a liar. The Doppler signal from Baekdu has been stable for the past 13 years, and a close examination of other signals did not reveal any other explanation for the signal. Halla is real – which brings us back to the question of how he survived being swallowed.

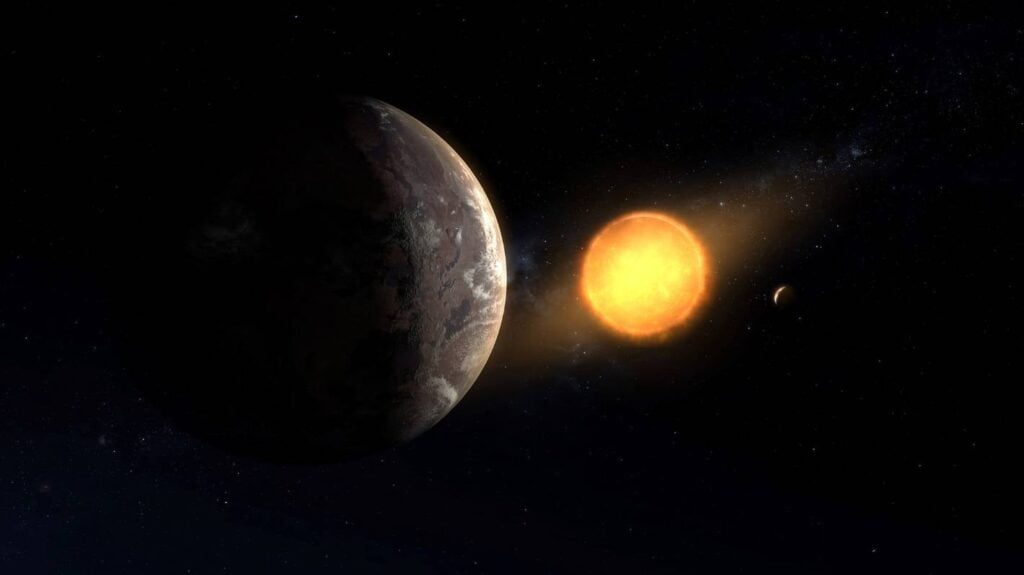

NASA/JPL-Caltech

K2-33b, shown in this illustration, is one of the smallest exoplanets discovered to date. It makes a complete revolution around its star in five days.

Two stars become one: how to survive

After confirming the existence of the planet, we came to two points that could explain what we are seeing with Baekdu and Halla.

About half of all the stars in our galaxy did not form independently like our Sun, but are part of binary systems. If Baekdu was once a double star, Halla may never have faced the danger of being surrounded.

The merger of the two stars may have prevented either star from growing to a size large enough to engulf the planet Halla. If one star were a red giant on its own, it would swallow up Halla – however, when it merges with another star it jumps straight into the helium-burning region without growing to reach Earth.

Alternatively, Halla could be a nascent planet. The violent collision of these two stars may have produced a cloud of gas and dust that would have formed the earth. In other words, the country of Halla may be the country of the newly born “second generation”.

Whichever explanation is correct, the discovery of a very close planet orbiting a helium-burning red giant star shows that the universe finds ways for exoplanets to appear in unexpected places.

Daniel Huber is an astrophysicist at the University of Sydney.

“This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.”

#Astronomers #surprised #planet #shouldnt #exist